We read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the great medieval English classic as our Christmas read over at the Catholic Thought Book Club. These are my comments and thoughts.

I’ve completed Part 1. What a joy of a read! I’m starting with the Marie Borroff translation since that is what I have as a hardcopy. It was included in the Norton’s Anthology of English Literature, Part 1, which I’ve had since undergrad, going back to the late 1980s! I keep my books and I try to keep them in good shape. If I read this fast enough I may try the Tolkein translation. I’m also listening to the Simon Armitage audiobook of his translation. It’s read by Bill Wallis, and I love the reading and sound of it. I’m considering getting Armitage’s translation itself. [Note: I did not read the Tolkein translation, but I get the Armitage translation to go along with the audiobook.]

###

I

should describe the poetic form of Sir

Gawain for those that might be interested.

It’s not that complicated. First,

it’s a narrative poem, so there is a story and narrative progression. It’s told in stanzas, and there are 101

stanzas to the poem. The stanzas are of

varying lengths of at least a dozen lines (I didn’t actually count) to as any

as two dozen. Each line, called the

alliterative line, is also of varying syllabic length. What controls each line are a regular number

of stressed syllables, four stressed syllables to each line but there is a

pause at the center of each line called a caesura. Caesura translates to cutting in Latin, and

so the pause creates a cut in the line.

Of the four stressed syllables, two come before the caesura and two

after. Let’s take an example. Here’s the eighth stanza from the Tolkein

translation.

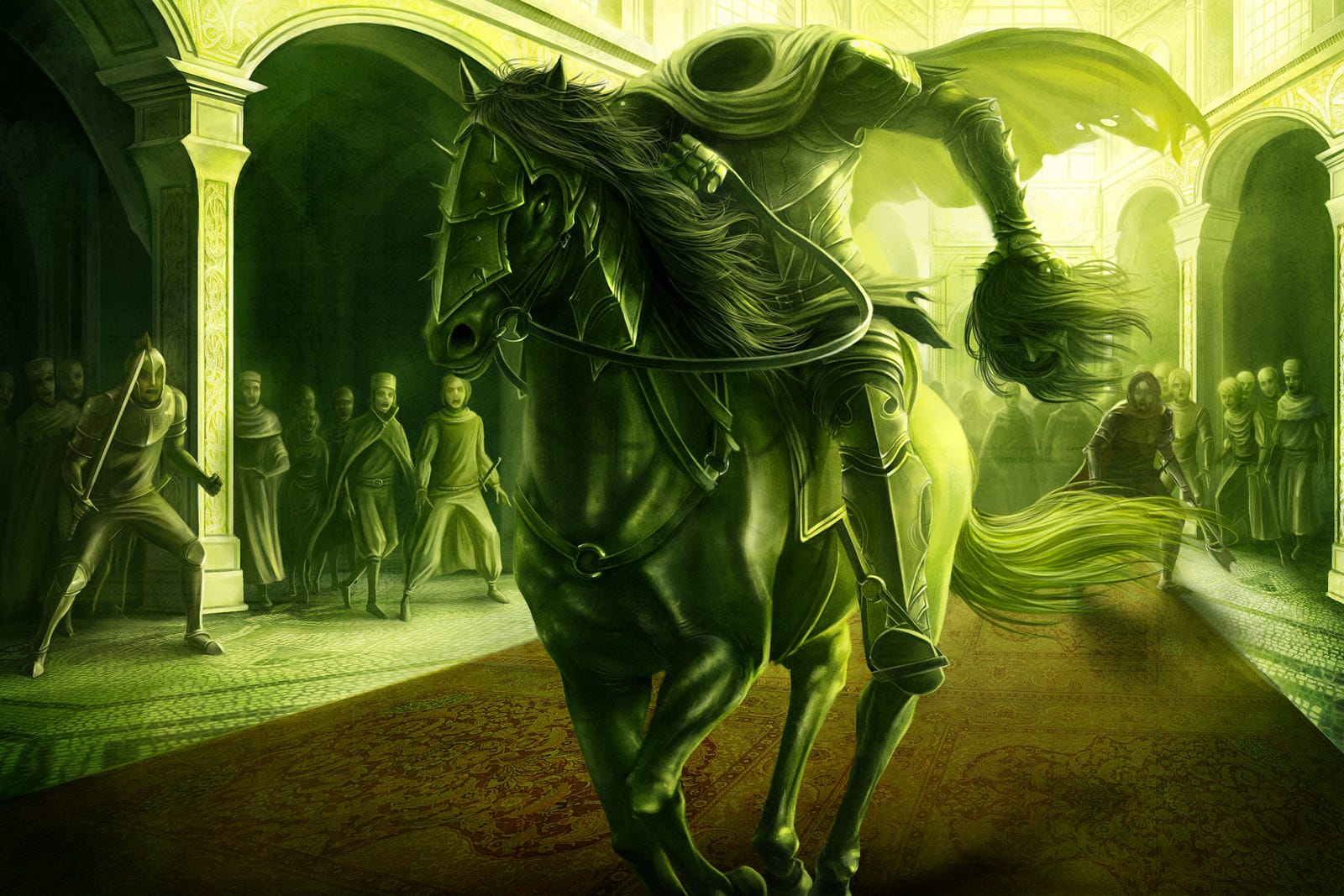

All of green were they

made, both garments and man:

a coat tight and close

that clung to his sides;

a rich robe above it all

arrayed within

with fur finely trimmed,

showing fair fringes

of handsome ermine gay,

as his hood was also,

that was lifted from his

locks and laid on his shoulders;

and trim hose tight-drawn

of tincture alike

that clung to his calves;

and clear spurs below

of bright gold on silk

broideries banded most richly,

though unshod were his shanks,

for shoeless he rode.

And verily all this

vesture was of verdure clear,

both the bars on his

belt, and bright stones besides

that were richly arranged

in his array so fair,

set on himself and on his

saddle upon silk fabrics:

it would be too hard to

rehearse one half of the trifles

that were embroidered

upon them, what with birds and with flies

in a gay glory of green,

and ever gold in the midst.

The pendants of his

poitrel, his proud crupper,

his molains, and all the

metal to say more, were enameled,

even the stirrups that he

stood in were stained of the same;

and his saddlebows in

suit, and their sumptuous skirts,

which ever glimmered and

glinted all with green jewels;

even the horse that

upheld him in hue was the same,

I

tell:

a green horse great and thick,

a stallion stiff to

quell,

in broidered bridle

quick:

he matched his master well. (ll. 151-178)

Let’s look at the first line: “All of green were they made, both garments and man.” The two stressed syllables before the caesura are “green” and “made.” The caesura comes right after the “made” actually punctuated with a comma, though caesuras are not necessarily at a punctuated pause. The two stresses after the caesura are “gar” from garment and “man.” Now we are dealing with a translation and the four stresses and caesura may not be as clear in the modern English as it would have been poet’s actual language.

There is an interesting little technique at the end of each stanza. The poetic line suddenly shortens into an appendage of five lines. The first of the five is only two syllables, and in this stanza is “I tell.” The four last lines form a rhyming quatrain. While the alliterative line goes back to Old English, this appendage, called the “Bob and Wheel” is something that came out of the late Middle Ages and out of hymns. The two syllable line is the “Bob” and the quatrain is the wheel. I really like the concept. It allows the reader to take a breath every so often, slowing the pace down, and providing a summary of what went before it.

The alliterative form was throw back by the time this poet was writing in around 1400. Since he did not come from the London area, the poet probably was more Anglo-Saxon or Welch, and perhaps felt this form was closer to his speech. Geoffrey Chaucer died in 1400, so he was writing before the Gawain poet, and you can see Chaucer’s poetic form is much more Romance language derived. So the Gawain poet is looking backward, reviving a previous form.

###

My

Reply to Joseph:

Joseph wrote:

"Kerstin, I read the Middle-English text and it's very alliterative. John

Ciardi's translator's note on Dante's Divine Comedy points out that,

"English is a rhyme poor language,"

I'm probably going to disagree with Ciardi here. Of course English is not a

rhyme rich language but many a poet through the ages have been using rhyme. It

hasn't stopped them. In my opinion, it's just natural for English to write in

alliteration. The language is just made for it, especially early and middle

English. So it's not because it's rhyme poor but because it's more natural to

the language. I think poets in English force themselves to rhyme.

My

Reply to Galicius:

Galicius wrote: "My

humble/honest input on this reading:

The rendering description in Chapter 2 will sound abominable to any vegetarian.

We have a member of the immediate family and have a few vegan and

vegetarian..."

I'm not a vegetarian, but even for me it was a bit revolting. Hunting and

butchering of animals is brutal, and I'm squeamish. You reminded me of a scene

in Tomas Hardy's novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles (if I'm remembering correctly)

where they slaughter a pig. It was Hardy's way of bringing in hard realities.

My

further comment on the hunting:

As I said, I'm

squeamish...lol. But I do eat meat and I'm aware of how it comes to the

supermarket and eating meat is human. Sometimes I feel like St. Francis of

Assisi with love for all animals. I have a little vocal prayer when I do see an

animal. I say, "Lord have mercy on all your creatures. They are also of

your heart."

By the way, as it happens

my dear cat has had to undergo a major procedure these last couple of days for

a blocked urethra. He had not urinated for around four days, and he was

probably close to kidney failure. He's currently recovering at the vet

hospital.

By the way, I should say,

there is nothing wrong with hunting. It's a necessary activity and hopefully

done for need rather than human glory.

My

Reply to Kerstin who pointed out the alternating of the

hunting and seduction scenes:

Good observation on the intertwining of the hunting and seduction scenes. I wonder if there is some metaphorical or symbolic connection? I guess Gawain is being "hunted." ;)

So is Gawain the hunted or the hunter? If he's the hunted, then he's able to survive the hunt. If he's the hunter, I can see he killed off the animal lust of the seduction. LOL. OK, so what's the metaphor? I don't see one. There may not be one. Perhaps it's just a neat dramatic device to intertwine the hunt and the seduction. However it still feels like there's a significance I'm missing.

###

Some

lovely quotes to sample the poetry.

First here are descriptions of the beautiful Bertilak’s wife and the old

crone beside her. These quotes will all

come from the Armitage translation.

She was fairest amongst

them—her face, her flesh,

her complexion, her

quality, her bearing, her body,

more glorious than

Guinevere, or so Gawain thought,

and in the chancel of the

church they exchanged courtesies.

She was hand in hand with

a lady to her left,

someone altered by age, an

ancient dame,

well respected, it

seemed, by the servants at her side.

Those ladies were not the

least bit alike:

one woman was young, one

withered by years.

The body of the beauty

seemed to bloom with blood,

the cheeks of the crone were wattled and slack. (943-53)

“The body of the beauty seemed to bloom with blood,/the cheeks of the crone were wattled and slack”

Here the Green knight’s court off on their first hunt.

On the bugles they blew

three bellowing notes

to a din of baying and

barking, and the dogs which

chased or wandered were

chastened by whip.

As I heard it, we’re

talking a hundred top hunters

at least.

The handlers hold their

hounds,

the huntsmen’s hounds run

free.

Each bugle blast rebounds

between the trunks of trees. (1141-9)

Here

in one of the attempts by Bertilak’s wife to seduce Gawain, and Gawian

resisting.

For that noble princess pushed

him and pressed him,

nudged him ever nearer to

a limit where he needed

to allow her love or

impolitely reject it.

He was careful to be

courteous and avoid uncouthness,

cautious that his conduct

might be classed as sinful

and counted as betrayal

by the keeper of the castle.

“I shall not succumb,” he swore to himself. (1170-6)

Here

where a servant leading Gawain through a forest points to the chapel where the

Green knight resides.

“I have accompanied you

across this countryside, my lord,

and now we are nearing

the site you have named

and have steered and

searched for with such singleness of mind.

But there’s something I

should like to share with you, sir,

because upon my life,

you’re a lord that I love,

so if you value your

health you’ll hear my advice:

the place you head for

holds a hidden peril.

In that wilderness lives

a wildman, the worst in the world,

he is brooding and brutal

and loves bludgeoning humans.

He’s more powerful than

any person alive on this planet

and four times the figure

of any fighting knight

in King Arthur’s castle,

Hector included.

And it’s at the green

chapel where this grizzliness goes on,

and to pass through that

place unscathed is impossible,

for he deals out death

blows by dint of his hands,

a man without measure who shows no mercy. (2091-106)

It’s

a pleasure to read and to listen to.

No comments:

Post a Comment